The following essay is from my graduate thesis at the Vermont College of Fine Art. The entire following narrative does not appear in the front portion of the thesis where images and text together tell a slightly different story about the Bethlehem Steel. The following would appear further back in the publication.

I grew up in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Bethlehem is home to the Bethlehem Steel Company. I never worked there, I never wanted to work there, but it was a looming presence in my life while I was growing up there. It was such a big company. It was a part of everyone’s life in Bethlehem. I do not live there anymore. I have not lived there for many years. But I remember it, sometimes very vividly.

Bethlehem is named after the biblical city in which Jesus was born. On Christmas Eve, 1741, thirteen German speaking Protestants, who immigrated and settled along a large river called the Lehigh, drew up a petition to name their town Bethlehem. There was little cause to concern themselves with paperwork and naming rights from state or the national governments because there was very little state or national governments back then. There was probably even less concern to run it by the native Minsi tribe, who were currently living on the land.

There is a borough of Bethlehem called Freemansburg. This is where I was raised. It is its own separate little community that felt both part and separate from Bethlehem. But like Bethlehem, it rested along the banks of the Lehigh River. Our fathers and grandfathers supplied part of the workforce for the Bethlehem Steel.

From where I lived in Freemansburg, you could see the Steel from my front yard and if you walked around the house to my backyard you could still see the Steel from there. All the locals referred to Bethlehem Steel as ‘The Steel’ or ‘The Plant’. You heard this so often when we were kids. Shortening the name of something that was spoken of so frequently during conversations always impressed upon me the intimacy that thing had in all our lives. Even as a child, you understood the power and hold of something that was so often referenced in adult conversations.

Bethlehem Steel does not exist anymore. No one works today for Bethlehem Steel. Check this. As a company it is non-existent. Even though it is gone, physical parts of it remain. Huge leftover structures still dot the landscape along the Lehigh River. They are brown, grey monolithic structures that stand as sort of grave markers for an industry that supplied a ton of work to our forefathers and a ton of steel to America’s infrastructures.

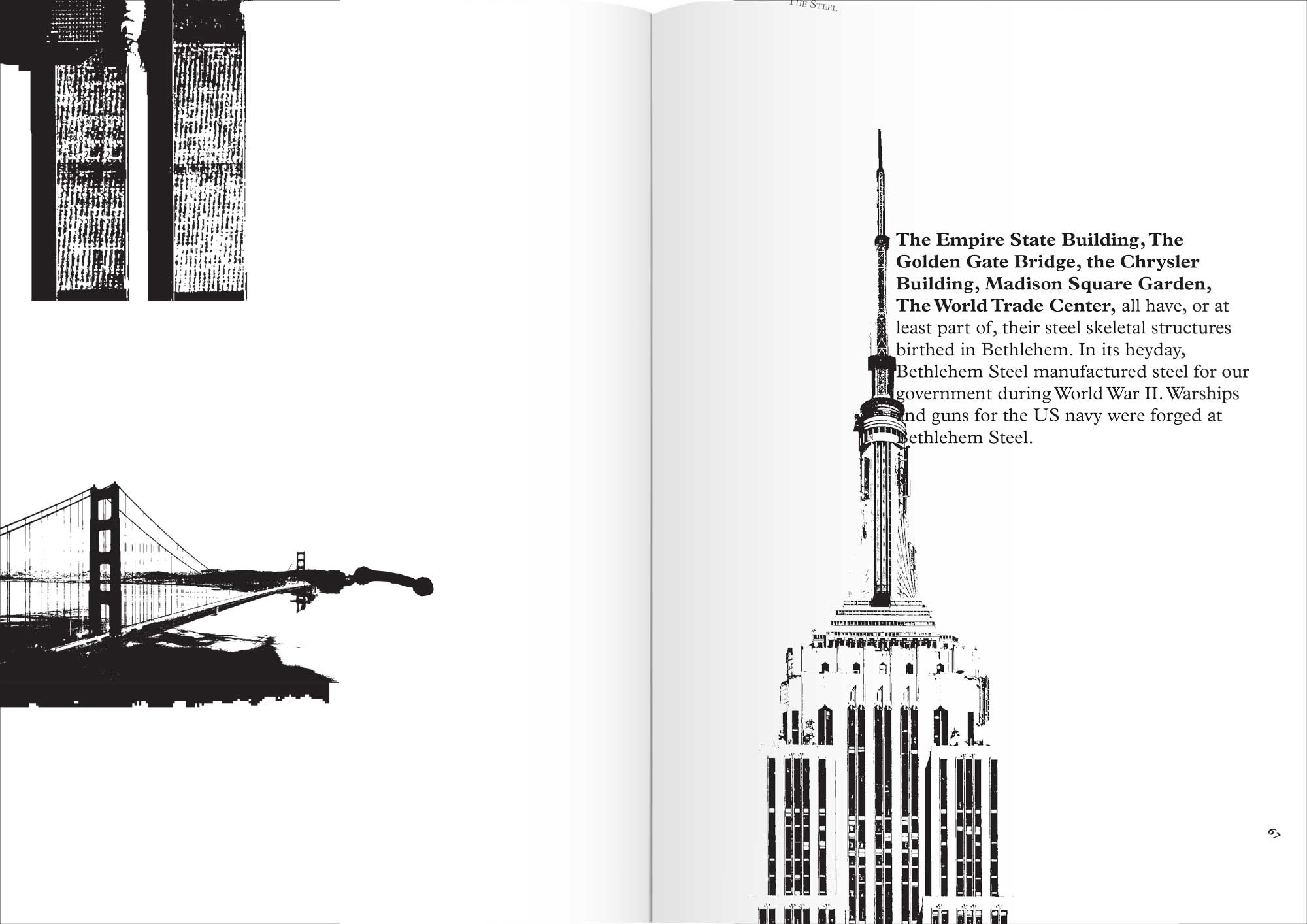

The Empire State Building, The Golden Gate Bridge, the Chrysler Building, Madison Square Garden, The World Trade Center, all have, or at least part of, their steel skeletal structures birthed in Bethlehem. In its heyday, Bethlehem Steel manufactured steel for our government during World War II. Warships and guns for the US navy were birthed at Bethlehem Steel.

I grew up no more than a mile and a half from there. I never imagined ever working there. And I would never be given the chance. Its demise began while I was in high school. Its final breath ended after I graduated from college. Its deathbed took so long to complete from when to when? that when I read the news of its last days and hours, it was less a feeling of nostalgia as it was a feeling of inevitability.

Before I left Bethlehem, it was still a big company. One could see it everywhere. The Steel Plant ran east and west three miles along the southern shore of the Lehigh River. Bethlehem’s borders grew and wrapped itself around its land and its structures.

In the middle of all that land, crossing the Lehigh River and bisecting the Plant itself is the Minsi Trail Bridge. It was a bridge that connected the north and south ends of Bethlehem and is named after a long ago path that ran along the Lehigh. The Minsi Trail, or The Great Minsi Trail as it was also known, takes its name from the Minsi tribe. The Minsi were one of the three subtribes of the Lenni Lenape. Hundreds of years ago they lived at the headwaters of the Delaware River, which was about sixty miles south of Bethlehem. Although history writes that the Lenni Lenape were the most warlike of the many local indigenous cultures, the Minsi were considered a peaceful people. What that means in America’s historical opus is that when it became time for the Minsi tribe to leave, they probably did so without much choice. Today, the Minsi are long gone from the area. The Steel, or what’s left of it, remains.

The Steel operated around the clock. I heard it. I lived close by. I heard it all the time. The Steel was a little over a mile from my home as the crow flies. One heard the constant drone of clanging metal and machines working day and night. It was far enough away that it was not intrusive, but it was close enough to be aware when the constant metal clanging would stop. Those pauses happened between worker shifts.

It was not only the noise that signified the changing of worker shifts. It was the thousands of workers coming and going at the same time that also did it. Three eight-hour shifts of work kept a constant rotation of employees going to work and coming home. Those shifts happened at 8:00 in the morning, 4:00 in the afternoon, and 12:00 midnight. The Minsi Trail Bridge was a conduit for a great portion of those workers who lived or parked their cars on the north side of the bridge and walked its span to work or to start heading home. The bridge was built for cars and foot. One knew those times of day without ever having to wear a watch. It was the lull of noise in the air and the mass of humanity crossing the bridge that let you know what time of day it was. It happened every day while I was growing up.

When crossing the Minsi Trail Bridge you realized so many things were of a giant scale there. On both sides of the bridge were a couple of massive, iron structures. They were huge outdoor mobile bridge cranes, called ore bridges. Two each stood on either side of the bridge. They ran perpendicular to the bridge’s length. The ore bridges spanned and looked down on an ore ??? yard. Here is where iron ore was sorted, stored, and moved prior to its use in the blast furnaces a quarter of a mile away.

Those structures looked like old railroad trestle bridges. They were about the size of ones you saw that spanned eight lanes of highway. They were suspended hundreds of feet off the ground, and they carried a crane that glided along the length of their bottoms. This crane’s function was to dip hundreds of feet down to the ore field, pick up the iron ore that was transported and dumped from incoming train cars, and then move the ore to other train cars that transported that load to the blast furnaces. What made these structures even more impressive were that they moved. They moved both parallel to the bridge and perpendicular to its length. That means as one was crossing the Minsi Trail bridge, you had a behemoth ore bridge traveling the same direction as you or in the opposite direction. If you could picture a railroad bridge that spanned a small river being able to move back and forth across that river and along its length as well, you would get a sense of the mechanics and raw power needed to move these structures.

One of those ore bridges is all that remain. Three have been torn down and what became of their material, God only knows ???. The remaining ore bridge has been removed from its original location and placed on a set of gigantic concrete piers. What is placed on the side of this structure is less befitting of the Steel’s demise and more a telling sign of economic, blue-collar placation in the twenty-first century, a giant neon casino sign.

Today, those neon lights spell out ‘Wind Creek’. A casino is now inside the site of Bethlehem Steel. The casino is owned by the Poarch Band of Creek Indians. It is a full-fledged casino. There are hundreds of slot machines, several entertainment complexes, and a hotel for gamblers. Those slot machines occupy the space where thousands of men and women helped make steel for this country. It is a good bet that even some of them, long retired and years away from their Steel experience, inhabit the floors of that gambling venue and feed a constant stream of coins into all those slot machines. The Bethlehem Steel began on the lands of an indigenous culture. And what remains of the Steel is owned by descendants of another indigenous culture.

To the east of the casino and at the far end of its property, out of sight from my home by at least a couple of miles, rested the coke works. 160-acres and an additional 30,000 workers were at this part of the Steel. Bake coal for 34 hours at a temperature of 2,000 degrees and you get coke. Coke is the material that can be burned to the extreme temperatures needed to create molten steel. Molten steel is used to create the various shapes and structures required to build bridges, skyscrapers, and ships.

The substances that flew into the air from the coke works were far from my neighborhood, and fortunately, the winds rarely blew towards our house. But those substances blew somewhere. Probably to this day, industrial remains from the coke works are mixed into the soil in some suburban development farther east of Bethlehem, or maybe somewhere in New Jersey, or even in the Atlantic Ocean.

But air currents being what they are some of it did make it to our neck of the woods. Compound that with went into the sky from other steel making processes and its evidence would show up in our neighborhood at certain times of the year.

It was not until my late teens, when I went to college, that I realized snow could stay pure white for days at a time. In our neighborhood, The Steel was the cause of enough air pollution that upon a day after a good snowfall, there were sprinkles of little black specs onto every snowdrift. As a kid, you didn’t think about those little black specs since you had seen this all your life. You realize when you finally see snow in some other location that those little black specs have been always floating around in the air. Breathe deep everyone.

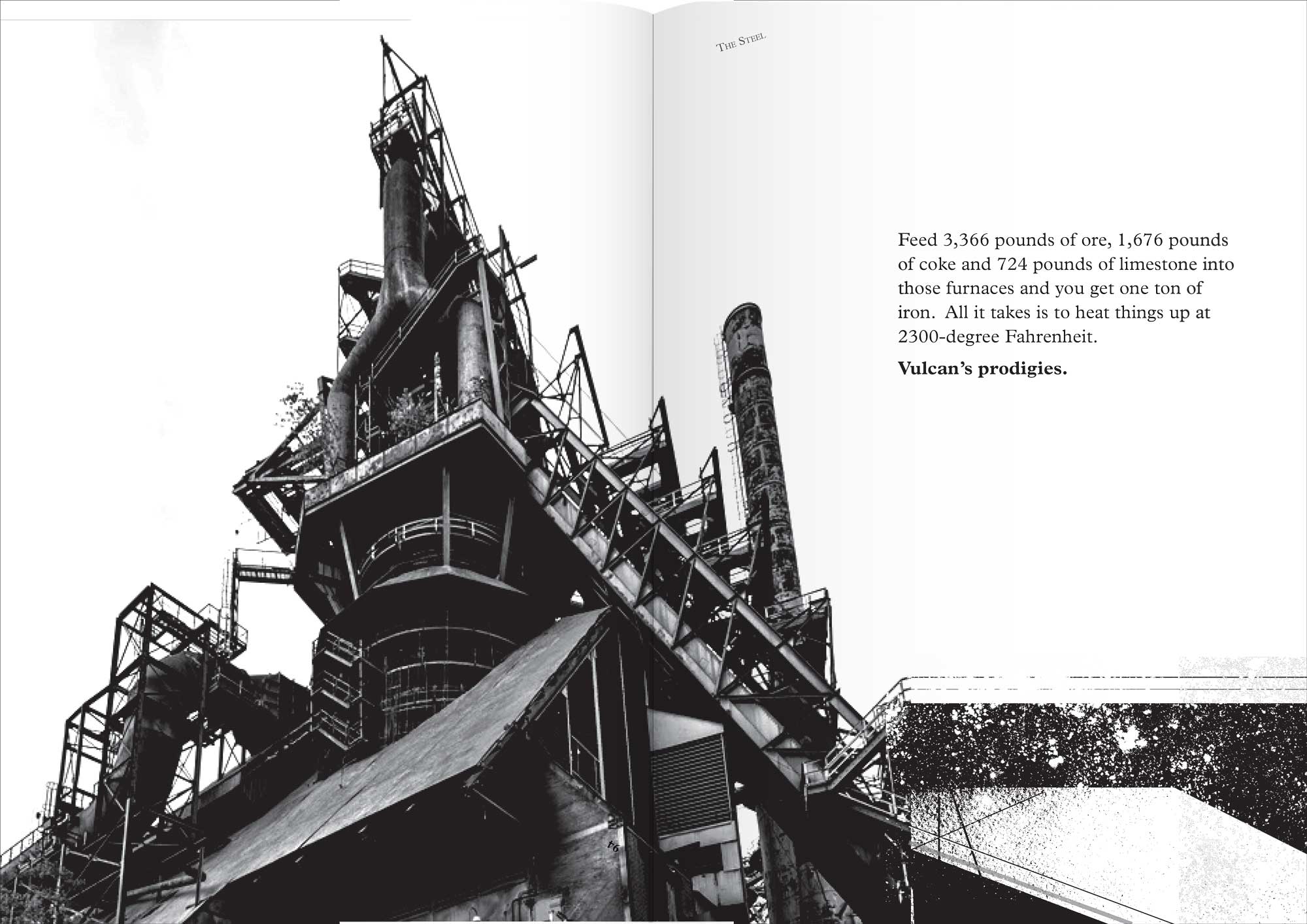

If you wanted to know where some of that other dirt in the air came from,

all you needed to do was travel back into the central part of Bethlehem are there sits five towering stacks of piping and metal constructs. They stand as watchful sentinels over Bethlehem. You see them along the skyline whenever you first drive into the area. They are both a reminder of present-day Bethlehem and a Bethlehem 100 years ago. They are the furnaces, the forges of steel making. It’s where the coke went. These towering monoliths were called the Steel Stacks.

They are over 200 feet tall. Five of them stand side by side almost a quarter mile apart from each other. The first of them was built over a hundred years ago. Those furnaces produced tons of iron every day. Feed 3,366 pounds of ore, 1,676 pounds of coke and 724 pounds of limestone into those furnaces and you get one ton of iron. All it takes is to heat things up at 2300-degree fahrenheit temperatures. Vulcan would be proud. Vulcan’s prodigies.

From my home you heard those furnaces run day and night. They would sound like someone had left a giant faucet of thick liquid running over a faraway pavement a few miles away. That sound mixed with the continuous rattling and screeching brakes of train cars that brought in the various mineral deposits into other parts of the Plant. This all made for a continuous cacophony of noise that was easily heard a mile and a half away to where I lived.

I never really heard it. It never bothered me. When I think back to that noise, I realize how acclimated I was to its constant droning. When I moved away from home to attend college, I was subjected to another kind of background noise. I lived in an apartment on campus in the middle of Philadelphia. Climbing up to my eleventh-floor window was the noise of traffic and people screaming at each other in the middle of the night. Whereas my roommate, who grew up in the suburbs of Connecticut, made mention of the irritable sound outside our windows, I never gave it a second thought.

Later in life, when I moved into the suburbs and experienced the quiet of a suburban neighborhood, I realized how much background noise was ingrained into my life. Silence in the suburbs has its own sound. It is a sound punctuated softly by the noise of other moments. Leaves rustling. Winds blowing through chimes. A cat howling. A car traveling down the street. Something brushing over the grass in our backyard. It took me a few weeks to get a good night’s sleep when I first moved there. It was just a different kind of noise, and a different kind of silence.

In Bethlehem, it was dark at night. I have lived for the better part of the past fifty years of my life in urban environments. There is nothing like the darkness I had when I was very young. Today, light pollution permeates almost all environments where a lot of people congregate together. When I was a kid, if you stayed out in my backyard long enough, you saw the Milky Way. As one’s eyes adjusted to the night, you saw stars gradually appear where there was darkness moments ago. Your eyes adjusted to the blackness. There was no dim glow from a local strip mall over the horizon. That was a few short years away. You could see stars, better than you can see them most places nowadays. Take a quick 30-minute drive up into the Pocono Mountains and you would really see stars. In my backyard you could see so many constellations, except when the forges ran.

The forges of Bethlehem Steel did not only make noise, but they also emitted their own wondrous, disturbing light. When those forges ran, they blotted most starlight out. They did not run continuously, they ran for perhaps 15 minutes every hour, my memory is fuzzy on that detail. But when they ran, they created an eerie orange glow against the black sky at night. For those fifteen minutes my friends and I could play cards in my backyard and effortlessly see every suit, letter, and number on a deck of cards. There was no need of a porchlight. No need of flashlights. No need of matches. However briefly, the Steel gave us the light.

The sunsets were another source of wondrous light. Almost every cloudless day growing up, there was an extraordinary display of banded colors viewed from my backyard. But all those yellows, red, oranges, and even purples had a sinister reason for existing. That which made all those specs in our snow, that which let us play cards in complete darkness for a brief few minutes during the night, also made spectacular sunsets. If you see something consistently all your life, you get used to it. It becomes a noticeable thing when it is missing. Air pollution makes gorgeous sunsets and I have never seen sunsets again like a saw on an almost daily basis on the west side of Bethlehem.

My grandmother and grandfather lived on the south side of Bethlehem. They also lived along one of the rail lines that came in from the west end of the city. Trains came in from all over the country bringing in additional minerals to help with the steel making process. These trains had locomotives that were enormous, and they could carry hundreds of train cars behind them. They travelled directly through neighborhoods at the time. Fortunately, they did so at an almost pedestrian speed, so I never heard of any train fatalities while visiting my grandparents, although over the years there probably were some. Some of the trains were so long and going at such a slow speed, that it might take them hours to pass a typical train crossing. One game that was played, not as dangerous as you would think, but dangerous all the same, was to put a coin on the steel rail when the train crossing signals began. You stood back and waited for the huge locomotive to pass. You watched its wheels and unfathomable weight roll over your sitting coin. After the train passed, you would be rewarded with a flattened and stretched coin, lost of all its engravings, just a shiny stretched thin piece of metal.

My grandparents’ home was just a block away from the train crossing. These slow-moving, gigantic behemoths shook the house when they passed. They vibrated the house. This is another moment that one grows up with and never really reflects on the bizarreness of the situation. A whole house vibrating as a locomotive passed. Heck, sometimes if there was something good on TV at the time, someone would get up and turn the volume up so we could hear the program over the locomotive vibrations. When the train passed, the volume got turned down and this was played out over and over again that no one ever gave it a second thought. The bizarreness of the situation became evident when someone was in the house and for their first time was in the middle of a rumbling home.

The 1960’s and 70’s, brought about the first wave of the environmental movement. The Bethlehem Steel was not immune to this. However, one hundred years of a steel making processes that were designed to enhance corporate profits was not going to undo the past one hundred years at a moment’s notice. I do not have a measurement of how successful the Steel was at curbing pollution in its final years, but during my later teenage years there were far fewer black specs in the snow and the sunsets were a bit less vivid. I was past the years of playing cards with my friends, so I never tested the available orange light in the backyard.

My father made his mark for the Steel by a happy accident. He was a draftsman. Unlike my grandfather before him, he was part of the white-collar workforce. Nine to five he went to work every day like clockwork. He had a parking lot for his car so his voyage across the Minsi Trail Bridge was never by foot. He wore a coat and tie every day. He was never dirty coming home.

My father was a draftsman for the pipe fitting operations throughout the Plant. Architectural and engineering drawings were in his lifeblood. One of the assignments he had was to plan out a piping system to help alleviate some form of pollution. How it did this is beyond me. That functionality could fit onto another hundred page document. But what made this job so wonderful and a happy accident was the fact that he was color blind.

You see, his piping system would run through the entire Steel and parts of it would even be visible as one crossed the Minsi Trail Bridge. The system also needed to be painted. And since this was the seventies his choice of paints was fairly expanded from previous years. Amongst the palette presented to him of browns, grays, and blacks, were colors that were inspired by the psychedelia culture of the time. Match this with his color blindness and the fact that color blind people do not readily see the intensity of certain colors, Bethlehem Steel wound up with a relatively thin neon blue piping system throughout all its brown and grey, rust colored buildings.

To me, this was the greatest thing in the world. It looked like a simple, colored, elegant line running through the course of this miles long plant. It was an accent to stand out against the drab. It was a beautiful moment of graphic delineation against a simple plain background. The contrast of colors made it seem like a small rebellion against the great polluting industrial complex.

It was also temporary. Not because of any uproar or upper management modifications, but because no matter how ‘clean’ you want to make the steel-making process, it is still going to be a dirty way of making things. It took no time at all for the neon blue to absorb all the colors of the pollution still being put into the air and very soon the piping blended into the brown-grey background of the buildings onto which it was attached.

I currently live and work in Duluth, Minnesota, which lies at the far west tip of Lake Superior. If you looked at that lake and envisioned a long forefinger pointing southwest, Duluth would be at its tip and at the top of the fingernail.

I have lived at various locations in the urban areas of Philadelphia and Boston over the past thirty-five years. They were great places to live, and I have fine memories there. But when I came here to Minnesota, and I started to meet people, I started to get a familiar feeling. There is no steel company here in Duluth, but there is industry along the shores of Lake Superior. There is not a river running through the city, but there is the lake right against its shores and its as big as an ocean from where I’m standing. There are no buildings here that remind me of Bethlehem or even Freemansburg. It’s just a feeling. You sense it from the ‘hellos’ you get from the dog. You sense it from the ‘How are you’s and the pause they give after the question to listen to the answer.